Chapter List:

Part 1: Be afraid. Then don’t be.

In the first installment, we examined the lesser horrors of Satan. These included the horrors of magic, with a focus in its many modern technological forms. But to grasp the Horror of Christ, we need to travel back to the time when he was born, and try to see magic through the eyes of the people who lived there.

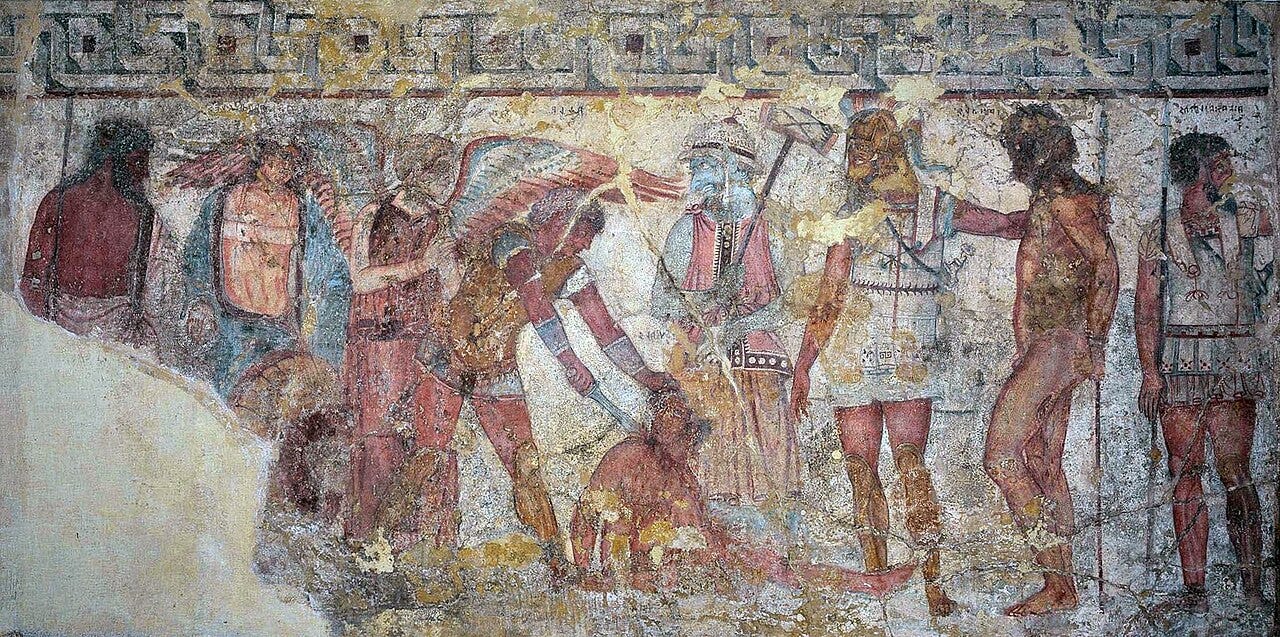

Viva Roma

How was Jesus Christ perceived in his day?

We can’t technically “know” the answer in the scientific sense, because the past is imaginary. The chain of custody for our evidence is riddled with gaps, and even so-called primary sources may be poisoned by unseen hijinks. No matter how diligently we collect and analyze our data, we cannot perfectly parse fact from fiction, post hoc editorial, or political propaganda. It’s hubris to assume we can.

This state of affairs shouldn’t be hard for moderns to grasp. After all, we are still subjected to secret schemes and coverups today, even in our era of mass media, global information networks, and consumer grade surveillance equipment. While we can engage in endless scholarly debates and speculation about past events, we shouldn’t fall into the epistemic trap of thinking we know what we can’t possibly know. When in doubt, we should instead rely on our artistic, intuitive sense of the world, and the fractally iterative stories that obtain within it.

With that in mind, let’s set our DeLorean to 1 AD, on the streets of Rome.

There are roughly 250,000 miles of those across the empire: layered marvels of gravel, lime, volcanic ash, forging concrete that can set while fully submerged. Gradient aqueducts like the Aqua Appia and the Aqua Marcia channel fresh water across a hundred miles with a precision that still puzzles modern engineers, supplying baths, fountains, and sewers for a million citizens. Sanitation works like the Cloaca Maxima flush waste away to the River Stynx, keeping Rome cleaner than future medieval cities. Public baths feature heated floors and intricate plumbing. Hot and cold running water in your home is a thing, if you had the denarii or the connections. A toga party at Casa Bisone’s in 2025 might not look all that different (minus the heated floors),

Arches, domes and multilevel apartment buildings showcase Rome’s structural genius. Her Colosseum seats 50,000 spectators, and features retractable awnings for shade. Surveyors use tools like the groma for pinpoint land measurements, and astrolabes to monitor the heavens. Practical maths power everything from tax collection to construction projects. The empire boasts cranes, water mills, and even early experiments in automation, like the steam-powered aeolipile of Roman Egypt.

The first century empire was also a triumph of commercial and social technologies. Sprawling from the shores of Britannia to the Nile delta, her leaders fashioned an ingenious administrative and legal framework which balanced cosmopolitanism, trade, and local interests with a strong central identity and civic order. Literacy rates among the general population are superior to those of out modern America public schools (a low bar these days, granted. But still impressive when compared to the rest of the world). The Romans generated great enduring works of philosophy, literature, and art, such that any education worth a damn is woefully incomplete without them.

In other words, Rome in 1 AD is a technological, scientific, cultural, and military superpower. We see reflections of our 20th century American empire in her legacy, including her tendency towards materialism and rationalism. She was not a “demon haunted world”, as Carl Sagan would have it, ruled by cargo cults shaking bones at the sky. The average Roman citizen believed in competence, ingenuity, virtue, law, technology, and scientific progress.

He also believed in magic.

It wasn’t only the hoi polloi who believed in magic. The highest ranking elites also did not perceive the supernatural as something fanciful or metaphorical, but rather as a mysterious (and often threatening) counterpart to normal forces and events. In this way, Pax Romana was far superior to the American version. The Roman citizen intuited aspects of reality that our modern particle physicists are only starting to realize. Namely: there is a point where all reductive models and language compression will simply fail to explain observable phenomena. The Romans understood that this gap of unknown mechanics was much vaster than any empirical theory could ever hope to account for.

How vast, exactly?

Well, as luck (or providence?) would have it, I stumbled across

’ excellent “Spirits and the incompleteness of physics” just as I was preparing to publish this article.1According to this paper2, the information stored in matter we understand reasonably well is roughly 10^89 bits, while the information in our patch of the universe is 10^122 bits. That is, the matter we think we understand decently represents a fraction:

10^{-33} = 0.000000000000000000000000000000001%

of the information content. Who knows, maybe this absolutely tiny subset of matter is described by particularly nice and tidy laws? There are good reasons to think so.

A much larger fraction of the observable universe's entropy is carried by supermassive black holes. This is about a quadrillion times larger than the amount of standard matter (but it’s still an absolutely tiny fraction—most resides in the unknown). Modern research on the holographic nature of quantum gravity suggests that black holes are intimately tied to chaos and the butterfly effect (classic paper). And there are very good reasons to believe that spacetime and thus locality becomes completely corrupted inside a black hole—good old Einstein's general relativity predicts this. This hints that you're reaching whole new levels of complexity, associated with the breakdown of locality. And locality is what made your laws so nice and tidy in the first place. But let’s say that physicists ramped up their experiments to measure about a (quadrillion)² times more stuff than what we have seen in the universe so far. Even then, if we kept finding locality, the best we’d get is an array of numbers encoding the laws of physics that still looks like this:

where the unknown might be highly irregular and dense. But at present, that green box represents a fraction of 10^{-33} of the rows, and only there do we know that the matrix is sparse, i.e. locality holds.

That is a whole lot of Unknown, and it hasn’t changed significantly over time. Among the depressing notions for ToE enthusiasts, it seems that the laws of physics “might be described by more numbers than you can store in the visible universe” (see the article’s footnote #8 for the calculation).

We could say something like, “Well, the ancients didn’t know anything about quantum mechanics or qubits.” That might be true, in the strict linguistic sense. But they knew of the Unknown, and knew it was much larger than the Known. Instead of shrugging it off, Rome allowed the information chasm to be filled with superbiological entities, to whom they would devote and supplicate for favor. As Cicero wrote in On the Nature of the Gods:

"Anyone pondering on the baseless and irrational character of these doctrines ought to regard Epicurus with reverence, and to rank him as one of the very gods about whom we are inquiring. For he alone perceived, first, that the gods exist, because nature herself has imprinted a conception of them on the minds of all mankind. For what nation or what tribe is there but possesses untaught some 'preconception' of the gods? Such notions Epicurus designates by the word prolepsis, that is, a sort of preconceived mental picture of a thing, without which nothing can be understood or investigated or discussed. The force and value of this argument we learn in that work of genius, Epicurus's Rule or Standard of Judgement. You see therefore that the foundation (for such it is) of our inquiry has been well and truly laid. For the belief in the gods has not been established by authority, custom or law, but rests on the unanimous and abiding consensus of mankind; their existence is therefore a necessary inference, since we possess an instinctive or rather an innate concept of them; but a belief which all men by nature share must necessarily be true; therefore it must be admitted that the gods exist. And since this truth is almost universally accepted not only among philosophers but also among the unlearned, we must admit it as also being an accepted truth that we possess a 'preconception,' as I called it above, or 'prior notion,' of the gods.3

In their adaptation from the Greek pantheon, the Roman mind also understood these metaphysical entities to persist in a domain of larger scale and complexity than what could be normally apprehended through the senses. I suspect this is why the Romans named the planets after their gods; they intuited that these objects were symbolically closest to the domain hierarchy they preconceived. This religious perspective wasn’t born of ignorance, but rather an indication that their minds were in a more a proper alignment than the modern atheist’s, with the Master maintaining some degree of control over his Emissary in his apprehension of the world. Operating in that mode of perception, they could see a little ways beyond the Veil between the local and non-local domains, and sometimes conduct limited transactions with beings on the other side.

Their depth perception into the supernatural domain might go far in explaining why Romans sycetized the Greek gods with their own, observing a consistency of being that preceded poetry or politics. It also might help explain their extreme and rapid dominance: the empire at her pinnacle wasn’t merely a superpower, but a sprawling hyperpower that chewed up tribes and spit out taxpaying citizens and soldiers. The notion that they were assisted by their gods in this wildly successful project wasn’t beyond the pale; indeed, to claim otherwise would have been seen as blasphemy. The Romans kept faith in their pantheon, and Olympus delivered.

For a while.

Cue ancient meme.

But before we tackle that, we need to try to better understand the minds of those who lived at the time of The Event. Using primary sources and our native intuition, we can model some of this mindset as it pertains to public displays of supernatural power, including those of Jesus the Nazarene. How would the average citizen of the time see and interpret his strange abilities? What effect would religion have on their observations, in a time when Jews, Samaritans, Zoroastrians, Egyptians, and pagan Romans often lived in close proximity? And if sorcerers, soothsayers, and Maji were a dime-a-dozen, what made Christ’s form of “magic” so uniquely dangerous that Rome spent the next three centuries in a doomed attempt to erase his followers?

To put it another way: How does one lowly, wandering magician conquer an empire without firing a shot?

Voodoo Economics

“Magic” is one of those words that has gained too many context-dependent definitions over time. It means too much.

For our purposes, I’ll define it this way:

An outcome that is lacking in sufficient causal explanation, due to hidden or supernatural mechanics involved.

I almost wrote “An effect without an observable cause,” but that would be going too far. Too many natural processes are difficult to observe and measure, yet seem to fall short of what most observers would call a “magical” outcome. The narrower definition above conforms to our common sense, covering everything from fancy card tricks, to psychopharmaceuticals, to MKUltra assassins, to Harry Potter zapping Whatizface with a wand. It might also encompass works like Giambattista della Porta’s Magia Naturalis, or the alchemical formulas of Enlightenment scientists, or basically any clandestine or pseudoscientific technique that deals with manipulating matter and/or consciousness in ways that aren’t fully understood or proceduralized. So let’s try to refine it further.

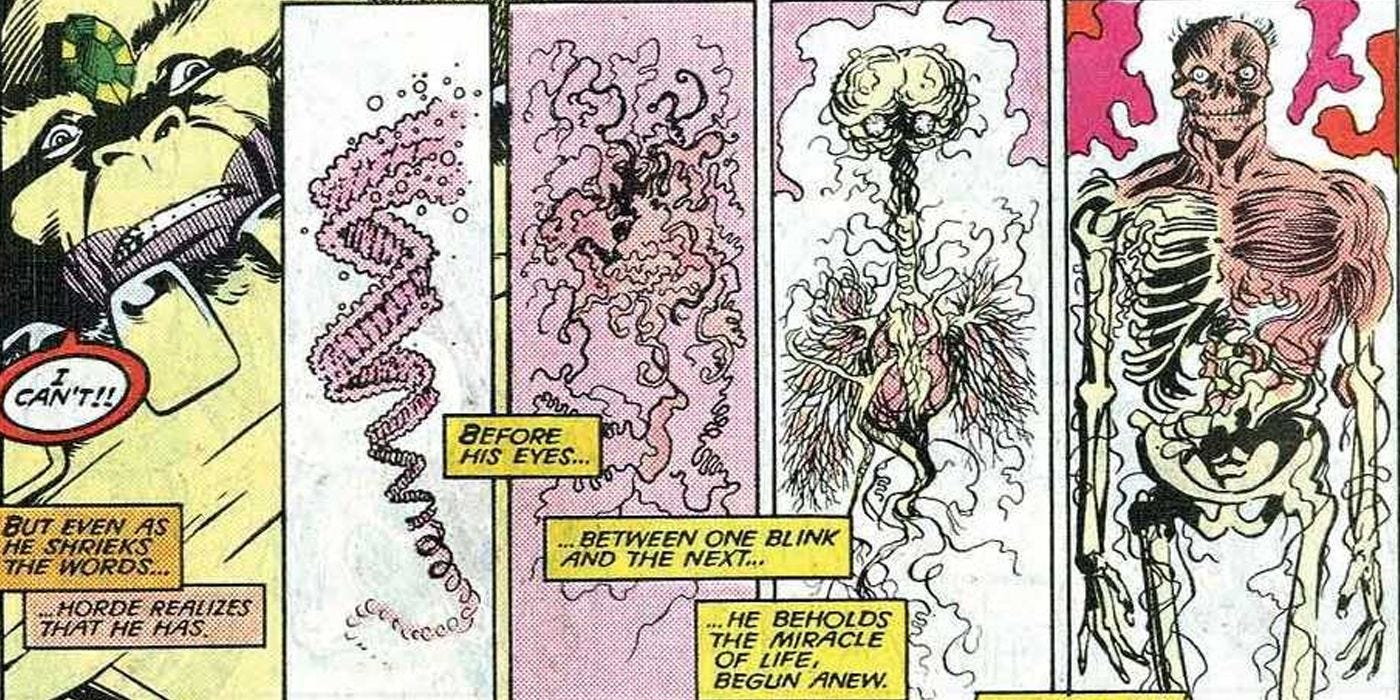

First, we could say that “real” (i.e. supernatural) magic results in an outcome that the normal observer not only can’t mechanically explain, but struggles to even theorize a framework of explanation. Second, we can say that the outcome is asymmetric in the sense that the inputs don’t account for the outputs by any stretch of the imagination.

For example: We might watch a magician pull a rabbit out of a hat and theorize a secret compartment, even if we can’t ourselves locate it with our senses. But if the same magician pulled the rabbit in half, and those halves then regenerated into two fully intact rabbits before our eyes, we would be properly stumped. Probably horrified, too.

We could perhaps differentiate these results in terms of science and art. For scientific magic, the unknown mechanics and physical components are purposely and strategically hidden from view (e.g. Penn & Teller, David Blain, a CIA black op, etc). For the art of magic, the mechanics are primarily linguistic and symbolic. The artist attempts to communicate with a non-human mind, with the belief that this mind will reach back.

According to every story ever told, across every known tradition, these minds will indeed sometimes reach back, and produce physically observable phenomena. The magical output can manifest in a variety of ways, depending on the inputs and goals of the minds involved. And because our bodies are constantly subjected to regular economic forces (e.g. thermodynamic, metabolic, etc), we assume that some kind of exchange must be taking place, if only to preserve the “law” of conservation.

Even without the aid of mathematical abstractions, we have a blood deep sense that energy/information is conserved during any transaction. This is likely due to resolution bias (i.e. mean observations of what is possible to accomplish with the known energy/information detected by our sensory organs). It also may be due to lack of a proper expertise or knowledge base; basically every gadget in your home would be widely seen as the output of witchcraft, not so long ago. Yet because we are curious, imaginative creatures, certain individuals would still likely theorize an empirical explanation for a Zoom meeting, even if it sounded pretty crazy on paper to the rest of us. A scientist of the Renaissance might imagine millions of brilliantly angled, illuminated mirrors and vaulted chambers, transmitting reflections and soundwaves across great distances (and he wouldn’t even be totally off base, metaphorically speaking).

When we see a human being act in a way that appears to bend the conservation rule, we’ll often apply labels like “genius” and “master” to the actor. When we see something that very clearly breaks it, we’ll either get very suspicious or fall to our knees in amazement. I suspect the magician violently multiplying rabbits with his hands would qualify in any age. It’s not just one rule that he’s breaking, after all, but several. For one thing, a rabbit isn’t a flatworm; its complex biology doesn’t lend itself to fragmentary reproduction. But even if it did, the speed of regeneration would require inputs and metabolic intensities unlike any force perceived in nature. There seems to be an energy debt that would normally be impossible to pay.

Due to this uncanny debt, the instinct for many religionists, supernaturalists and parapsychologists seems to be to invoke some form of unobserved energy source (e.g. psi, prana, mana, teotl, qi, the life source, etc.). In other words, like gasoline or yellowcake uranium, the conscious exercise of magical power requires some sort of currency as fuel. The magician pays the debt by drawing from this pool in some fashion, whether internally from his own supply or externally from some other living being.

First question: Does this fuel source have a moral property?

Most magic-believing cultures throughout history appeared to think so. But the landscape of moral economics is often alien to our sensibilities. For instance, to juice up your mana gas tank in ancient Hawaii, you may reasonably perform a human sacrifice to Kūkaʻilimoku or other muckety-mucks at your local luakini heiau. Payment options include: strangling, clubbing, bloodletting, immolation, and disembowelment.4 Bonus points for consuming the victim’s flesh afterwards.

Why is Mark picking on Hawaiians?

Fair enough. After all, the history of planet Earth offers an endless smorgasbord of human sacrificial rites. It would be much more difficult to locate a culture that did not practice this form of magical debt repayment, at some time or another (and, as we’ll see, the practice continues to this day under many euphemisms and disguises).

The sorcerer believes transactions of this kind can be judged as either good or morally neutral, even if they clearly break one or more of The Rules. For him, any moral significance would be located in his own motives, and not subject to external judgment of his means or methods. Absent even that moral restraint, only the result of the transaction would be significant: Was the payment deemed acceptable or not? If so, the entity has demonstrated its power, and can be relied on for future trades. The spell’s effect is essentially a market signal.

That’s not to say all of history’s magicians were amoral or evil, mind you. Recall that the Maji who visited the infant Christ were (likely Zoroastrian) magicians of the East, investigating a cosmic anomaly. And while the vast majority of neo-pagans come off like syncretic antichristians playing dess-up, certain individuals I’ve interacted with still seem to perceive the world in terms that a Christian might find somewhat familiar. I think the reason for this familiarity can be found in scripture (and particularly in one story, which appears every Gospel but Mark). But, much like the ramblings of utopian communists, the concept of “free” magic is as delusional as zero-point energy or perpetual motion machines.

(You might read such a bold claim and think, “Doesn’t every rule have an exception that proves it, Mark?” Yes, and it did. We’ll get there.)

This economic perspective on magic was widespread around the time of Christ’s visitation, albeit somewhat tempered by imperial virtues and politics. But while the first century pagans of religio Romana probably would’ve frowned on Hawaiian shark-god luaus, they weren’t so far removed from the practice themselves. Moreover, the Roman empire didn’t so much abandon human sacrifice as they adapted it into a civic form. Much like their borrowed pantheon, the Greek version of pharmakos was strategically tamed and abstracted to befit the Roman’s martial mindset and style of rule. For example. the victim might be afforded a chance to speak on his own behalf before the sacrificial rite was carried out. This legalistic format crafted an illusion of the supremacy of reason, with the human judge supplanting the thirsty god. But the desired social outcome was largely the same; mollify and reunite the people by releasing a pressure valve.

Christ’s execution was the apotheosis of this form of technocratic scapegoating, in which every participant in his murder, pagan and Jew alike, was allowed to rinse some blood from their hands. This practice would accelerate over the decades and centuries following Christ’s departure, culminating in a emperor whose democidal campaign would send the old gods into retirement. More on this ironic result later.

For now, here’s a theory of mine that I’ve never heard offered before:

The reason pagan Rome ultimately could not salvage Olympus is that Christianity was more similar to their religion than it was to the Semitic, Germanic, and (most) Indo-European faiths of the time. By this, I don’t just mean its philosophic similarities with Platonism, but the spiritual dimension of the faith as it pertains to the various intermediary beings and hierarchies of the non-local domain. The difference for pagan Rome was more a matter of range and vector than of kind. They could see upwards and outwards into the supernatural domain, but only to a certain distance, and with some confusion about which direction they were looking.

An early pagan exception to this rule would reveal himself in Capernaum, which is a story that we will need to investigate at length later in this series. Suffice to say that, unlike the by-then utterly debased and Satanic Judaism into which Christ was born, Rome’s pagans were already exposed to many of the virtues that he would teach, and so their empire marked a logical entry point for his mission. Roman participation in his murder was only the start of another lesson, which would eventually be completed along the banks of the river Tiber three centuries later. First, they needed to fulfill their essential role in the story: barbarians disguised as bureaucrats.

But the empire’s forms of legalistic barbarity and social control did not supplant their belief in magic, or the power of the divine. And so when first and second century Roman historians included supernatural events in their official accounts, they felt no need to evaluate the particular mechanics or source. They reported them bluntly, and mostly left it to the reader to interpret whether the cause was a sorcerer’s spell, a god’s favor, or some combination therein.

For example, in his Pompey chapter of Lives, Plutarch’s account of the bello civili includes omens and supernatural events, and records both Pompey and Gaius Julius as eyewitnesses.

But they went on soliciting and clamoring, and on reaching the plain of Pharsalia, they forced Pompey by their pressure and importunities to call a council of war, where Labienus, general of the horse, stood up first and swore that he would not return out of the battle if he did not rout the enemies; and all the rest took the same oath. That night Pompey dreamed that as he went into the theatre, the people received him with great applause, and that he himself adorned the temple of Venus the Victorious, with many spoils. This vision partly encouraged, but partly also disheartened him, fearing lest that splendor and ornament to Venus should be made with spoils furnished by himself to Cæsar, who derived his family from that goddess. Besides there were some panic fears and alarms that ran through the camp, with such a noise that it awaked him out of his sleep. And about the time of renewing the watch towards morning, there appeared a great light over Cæsar’s camp, whilst they were all at rest, and from thence a ball of flaming fire was carried into Pompey’s camp, which Cæsar himself says he saw, as he was walking his rounds.5

The histories of Rome don’t begin and end with prophetic nightmares and enchanted fireballs.6 Numa Pompilius, founder of the Vestal Virgins, is initiated in the ways of the Egyptian heka.7 Caligula dabbles in love spells. Nero summons Persian necromancers to appease his mother’s ghost.8

The point is there was plenty of magic to go around (and a dearth of Amazing Randy-type skeptics to debunk it). Even if we ignore archaeological evidence and only consult the official biographies of her elite, we could easily extrapolate the views of Rome’s average citizen, for whom the existence of effective amulets, potions, sorcerers and spells was widely accepted as a feature of daily reality (Andrikopoulos 2009). Various forms of astrology, divination, and evocation weren’t merely consigned to the fringes of the marketplace, like the Tarot joints that speckle New York City, but were rather integrated into the fabric of mainstream social life. If some witch put a hex on you, you had a boatload of options to relieve it (and maybe a means to curse your enemies right back, if you could afford it and keep the transaction relatively quiet).

Even as late as 3rd century AD, the fundamental belief in magic wasn’t restricted to the common man-on-the-street, but extended to the highest ranks of authority and power. Such high social status did not translate to greater success, mind you; due to magic’s asymmetry and occulted techniques, even an emperor could find himself on the losing end of it.

In the Vita Elagabali there is a less ghastly, but equally interesting story about Marcus [Aurelius Antoninus]’ involvement with magicians. It is read therein that Marcus had brought the Marcomannic war to a successful end by the assistance once again of the Chaldeans who subdued the Marcomans by means of a ritual and a spell (consecratione et carminibus), so that they would be eternally devoted and friendly to the Roman people. The context of the story is that Elagabalus, intending to start a war with the Marcomans, learned of this and was searching for the material components of the spell, which was apparently some kind of defixio, a curse tablet, in order to destroy them and end the effect of the spell and the peace it secured. The location of the defixio was not revealed however and Elagabalus failed in his quest to start a new war with the Marcomans. As an aside, this remarkable story would have us think that the imperial Chaldeans were at least imagined as an organisation with a certain degree of continuity and autonomy; several decades and vicissitudes of the imperial throne after the supposed end of the Marcomannic war by magical means, the Chaldeans of the time of Elagabalus still knew the nature and location of the defixio of Marcus and were able to suppress any information about it from Elagabalus.9

If the notion of emperors scouring the land for curse tablets sounds ridiculous, recall that these elite beliefs and practices remained continuous through the feudal mystery cults of Europe, to 19th century Theosophists and Freemasons, to our current age of “spirit cooking” chefs de cuisine like Marina Abramovic. Throw a dart at history and you’ll skewer a U.S. president who consulted an astrologer, medium, psychic, or all three. And lest you think it’s limited to Tarot readers in the White House or Kabbalists in smoky backrooms, nominal “Christians” get in on the magician rage as well. From snake handlers to gibberish-spouting faith healers to “prosperity gospel” scam artists, the economic theory of magic persists under every label and costume you could imagine. The lyrics change, but the song remains the same.

When our modern, materialistic minds try to grapple with this continuity of magical thinking through the ages, they might run straight to the toolkits of behavioral psychology and the social sciences for answers. The more conspiratorial minded might add that these strategies are well-understood and deliberately employed by the powerful, and that their external “beliefs” are just part of a camouflage they employ. But a cult has many hidden rungs, and many circles of initiation. When an exposure occurs, bear in mind that you might be looking at the tail instead of the dog.10

In any case, what was once widely considered a wise strategy to keep magical powers close at hand is now widely mocked as superstition. But what does the word “superstition” mean? What is its provenance?

How did the people of Rome use it, at a time when magic meant something more than secret compartments and card tricks?

Supersitio Maleficae

While the Romans considered magic a part of whole reality, that isn’t to say they were fans of it. It was viewed with skepticism and suspicion, even discounting the many charlatans who surely flooded the marketplace. Effective magic that fell outside the narrow band of the state religion “was conceptualized as an improper way of conduct of humans towards the divine” (Andrikopoulos 2009). Even astrology and divination were viewed as potentially illegal practices, subject to various regulations and measures. The picture that emerges through various imperial accounts is one where magic, science, religion, and politics co-existed, but were not considered co-equals. Being accused of sorcery could mean more than your “social” death.

After all, veneficia is alternately defined as “magical act” and “poisoning”, indicating the uncertainty of mechanical cause when dealing with a curse. If an important person falls mysteriously ill, questions arise. Was it the product of a magician’s arcane words and symbols? A furtive application of chemicals to food or drink? Some combination of both? If a reliable cause or agent wasn’t produced, the magician’s damage could expand beyond the physical and personal, into the realm of the social and political. A plague of suspicion would creep through networks of family, friends, and business associates.

Christ’s earliest followers weren’t exempt from this view of integrated-yet-suspicious magic. Indeed, one of the key charges lodged against Jesus by the Pharisees was that of sorcery, born of demonic trades:

Then they brought him a demon-possessed man who was blind and mute, and Jesus healed him, so that he could both talk and see. All the people were astonished and said, “Could this be the Son of David?”

But when the Pharisees heard this, they said, “It is only by Beelzebul, the prince of demons, that this fellow drives out demons.”

— Matthew 12:22-24

So the acceptance of magic as a “real” phenomenon didn’t often translate to acceptance of its practice or practitioners, even among Jews and non-pagan Gentiles in the empire. The pertinent questions weren’t technical (“How did he pull it off?”) but accessorial (“Which god (or devil) helped him do it?”). And like any expression of asymmetric power, it drew the attention and ire of established power structures.

This seemed particularly the case in mid-first century Rome. With the empire in turmoil and poised on the brink of another schismatic civil war, any form of poorly understood power seen as a potential challenge to the empire’s leaders or their gods was to be ruthlessly crushed. As Suetonius writes of Nero’s draconian regulations in Twelve Caesars, the early Christians fit this definition well enough to warrant their own mention.

Many things were both strictly regulated and restrained under his rule, and no fewer were established: a limit was imposed on expenditures; public banquets were reduced to simple distributions; it was forbidden for anything cooked to be sold in taverns except pulses or vegetables, whereas previously every kind of delicacy was offered; the Christians, a class of men given to a new and mischievous superstition, were subjected to punishments; the antics of charioteers, who, with long-standing impunity, roamed about deceiving and stealing as if it were a game, were prohibited; the factions of pantomime actors, along with the actors themselves, were banished.11

Note that in the context of the period, superstitio did not correspond to our modern definition of “superstition” (e.g. a false belief based on ignorance and/or tradition). It was rather used as a contrast to religio, referring to the official state religion of pagan Rome and its legal priority. In other words, supersitito was a catchall to connote alien practices deemed potentially threatening to the civic faith, and its corresponding political order.

This didn’t always necessarily translate to violent action against the religious offender. As with astrologers, soothsayers and other sagae-adjacent woo-dealers, it sometimes marked them as individuals to be co-opted by the powerful for advantage. We might be seeing a bit of this strategy play out in accounts of the Samaritan sorcerer Simon Magus (aka “The Father of Gnosticism). Some accounts imply informal or at least sympathetic relationships with Roman officials.1213 Meanwhile the more dramatic and mythic versions of Simon sound like something J.K. Rowling or George Lucas might dream up.

XXXII. And already on the morrow a great multitude assembled at the Sacred Way to see him flying. And Peter came unto the place, having seen a vision (or, to see the sight), that he might convict him in this also; for when Simon entered into Rome, he amazed the multitudes by flying: but Peter that convicted him was then not yet living at Rome: which city he thus deceived by illusion, so that some were carried away by him (amazed at him).

So then this man standing on an high place beheld Peter and began to say: Peter, at this time when I am going up before all this people that behold me, I say unto thee: If thy God is able, whom the Jews put to death, and stoned you that were chosen of him, let him show that faith in him is faith in God, and let it appear at this time, if it be worthy of God. For I, ascending up, will show myself unto all this multitude, who I am. And behold when he was lifted up on high, and all beheld him raised up above all Rome and the temples thereof and the mountains, the faithful looked toward Peter. And Peter seeing the strangeness of the sight cried unto the Lord Jesus Christ: If thou suffer this man to accomplish that which he hath set about, now will all they that have believed on thee be offended, and the signs and wonders which thou hast given them through me will not be believed: hasten thy grace, O Lord, and let him fall from the height and be disabled; and let him not die but be brought to nought, and break his leg in three places. And he fell from the height and brake his leg in three places. Then every man cast stones at him and went away home, and thenceforth believed Peter.

But one of the friends of Simon came quickly out of the way (or arrived from a journey), Gemellus by name, of whom Simon had received much money, having a Greek woman to wife, and saw him that he had broken his leg, and said: O Simon, if the Power of God is broken to pieces, shall not that God whose Power thou art, himself be blinded? Gemellus therefore also ran and followed Peter, saying unto him: I also would be of them that believe on Christ. And Peter said: Is there any that grudgeth it, my brother? come thou and sit with us.

But Simon in his affliction found some to carry him by night on a bed from Rome unto Aricia; and he abode there a space, and was brought thence unto Terracina to one Castor that was banished from Rome upon an accusation of sorcery. And there he was sorely cut (Lat. by two physicians), and so Simon the angel of Satan came to his end.14

Whether or not a crowd watched an actual Jedi duel in the Forum, it’s clear that some second century writers felt confident their readers would at least accept the possibility of this. But, as with the anonymous author of Acts of Peter, such writings might still constitute a kind of underground samizdat of that time period. To describe a supernatural event outside the context of official Roman record was generally a dangerous thing to do, particularly given the wild turnovers and reversals of fortune that marked the era.

But to describe magic in a Christian context could prove suicidal no matter which emperor was in charge, due to its growing popularity among non-Jewish populations and its usefulness as a scapegoat in the recent past. In Suetonius’ original text, the words superstitio and maleficae used in conjunction imply a form of functional black magic (maleficium) without explicitly saying so, probably because it would have painted a target on the writer’s head in the time of Pax Romana. Rome’s elite were in danger of conversion, even at this early stage, and so any wording that could be perceived as challenging the supremacy of Olympus needed to be decorated with as much slander as possible. Christian were to be depicted as a threat, yes, but mostly because they were so vile and disgusting.

His contemporary Tacitus took much the same politically cautious approach to describe the gathering Christian threat in his Annals.

But neither human effort nor the emperor’s generosity nor the propitiation of the gods could banish the sinister belief that the fire was the result of an order. Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judaea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their center and become popular.15

The use of flagitia (“abominations) looks of a piece with Suetonius’ superstitio maleficae and Pliny the Younger’s superstitio prava et immodica (“perverse and extravagant superstition”)16 Due to the Eucharistic sacrament and the unseemly inclusion of women in Christian worship and rites, rumors of cannibalism and witchcraft were spread around liberally. But, while they still evoked illegal magic, the official labels applied were pejorative enough to diffuse any suspicion that the pagan gods of Rome could ever be challenged, let alone overthrown, by these “mischievous” new upstarts.

Of course, this is what would ultimately happen, fewer than two centuries later. But before history turned on that epic fulcrum near the bridge of Milvian, the disciples of Jesus would be hunted ever more aggressively, and subjected to the most grotesque forms of torture and murder. But instead of quashing the rival faith, this bloody government-sponsored campaign only managed to drive certain actors and activities temporarily underground.

Then came Marcus Aurelius, The Thundering 12th, and what just might be the most controversial rainstorm of all time.

Thanks for reading. The next chapter will complete the arc of Rome’s doomed war against Christianity, then return to the source of its defeat. If my pagan friends find themselves offended by what I’ve written so far, I would suggest you hold your fire until then. You might be surprised at what I have to say.

The Cat Was Never Found is a reader-supported blog. I don’t publish much paywalled content, so your generous patronage is very much appreciated.

P.S. If you found any of this valuable (and can spare any change), consider dropping a tip in the cup for ya boy. It will also grant you access to my “Posts” section on the donation site, which includes some special paywalled Substack content. Thanks in advance.

I highly suggest you read it all, even if you have no background in physics.

Egan, C. and Lineweaver, C. (2010) A Larger Estimate of the Entropy of the Universe. The Astrophysical Journal, 710, 1825. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/710/2/1825 [link]

Cicero, De Natura Deorum, trans. H. Rackham, Loeb Classical Library 268 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1933), 1.17.44.

Watts, Joseph (2016), Why Did Early Human Societies Practice Violent Human Sacrifice?, The Conversation [link]

Plutarch. Life of Pompey 68.2–3. Translated by John Dryden, revised by Arthur Hugh Clough, in Plutarch’s Lives, Modern Library, 2001

Indeed, the most famous supernatural events of Gaius Julius’ life come near the end of it, as he ignores the soothsayer’s grim portents.

Plutarch. Life of Numa 15.3–4. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin, Loeb Classical Library, 1914.

Suetonius. The Lives of the Twelve Caesars 6-34. Translated by J. C. Rolfe. Loeb Classical Library Edition, 1914 [link]

Andrikopoulos, Georgios (2009), Magic and the Roman Emperors, [Doctor of Philosophy dissertation, University of Exeter] [link].

As always, I would council my dissident atheist friends against projection. It’s one thing to not believe in the supernatural, but it’s a grave error to assume that your enemies share that disbelief.

Suetonius. The Lives of the Twelve Caesars: Nero 16.2. Translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library, 1914

Justin Martyr. First Apology 26. Translated by Thomas B. Falls, Fathers of the Church, Catholic University of America Press, 1948.

Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1.23, Translated by Alexander Roberts and William Rambaut. From Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 1. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1885.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. [link]

Acts of Peter 31–32. Translated by J. K. Elliott, The Apocryphal New Testament, Oxford University Press, 1993, pp. 427–428.

Tacitus. Annals 15.44. Translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb, 1876.

Pliny the Younger. Letters 10.96. Translated by Betty Radice, Loeb Classical Library, 1969.

Great article. I'd say the modern mix of hermeticism, gnosticism and theosophy that infects our academia and is one of the culprits behind the more recenct blindness of scientists to what science is and what it can do is more akin to Jim Jones's cult following and structure than to what the ancient roman and greek elites believed. Also, for some reason the unkown physics reminded me of a crackpot theory that my sister told me about 20 odd years ago: ghosts could go through walls because they were made of much denser material than matter.

Thoughts.

1. With regards to Cicero's, 'On the Nature of the Gods.'

His thought reminds me of Alvin Plantinga's philosophical premise of a properly basic belief. In short, there are epistemic beliefs about reality that are basic, or pre-logical to all humans that are rational to hold. Belief in God, that reality is 'there,' and many more function as basic beliefs. In this sense, while the atheist is often the one who assumes that the Christian is the one who needs to justify their beliefs, in fact, it is the opposite, that the atheist needs to provide some sort of justification or belief for why or how God does not exist.

2. The intelligence of the Rome: Moderns, blinded by their pride, are in effect retards compared to the ancients in many ways.

3. On Magic. I wrote a paper entitled, 'The Similar Function of Magic and Science,' which, as the title suggests, argues modern science is the 'new' magic of our present age. Both science and magic seek to change the natural world according to personal desire and will; the same effect, except perhaps different causes.

For anyone interested:

https://open.substack.com/pub/pjbuys/p/the-similar-function-of-modern-science?r=1ljcm3&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

4. You insulted Kūkaʻilimoku. How dare you.

5. The interaction of Peter and SImon Magus blew my mind. It reminded me of a story a Christian missionary to the Philippians told us at church one time.

At one of the villages, there was a well known sorcerer that people gave a lot of money to. The witch would publicly kill himself, usually by cutting. The body of the witch would lay dead in the middle of the street for three days, until, on the third day (see?) he would pop back up, fully alive. The witch had a lot of power, but the missionaries had enough with his blasphemy. The missionaries collectively prayed at the man for a week until, one day, the witch had an encounter with Yeshua. God met the witch and told him, 'you no longer have any power.'

The witch became a normal pleb, and, so amazed and terrified by his encounter with the Lord, he repented, and became a fellow missionary of the people who prayed for him.

Pretty cool and wild story, to which I have no reason to doubt it to be false.

Anyways, great article Mark. Looking forward to more soon.