When I was a kid, a video game was still something you mostly played in an arcade.

Yeah, I’m that old. You kids stay off my lawn!

Anyway, last week I was recounting some of those experiences to a friend. I mentioned how they were essentially magnet schools for juvenile delinquents like ourselves. We reminisced on the delicate protocol of placing quarters on the dash to reserve a game, and how some of us used drilled out slugs and fishing line to steal more time on the machines. Not me, of course.😉

What we failed to talk about was the sound of it; the icy jingle of coins and chiptune anthems, the machine gun rattle of the pinball bumpers, the sailor words and victory yelps, all of it half-drowned in the roar of blips, bombs, klaxons and laser beams.

The look of most arcades I played in was similarly anarchic and violent. They were like dark caves spattered with spooky bioluminescent geometries, blasted helter-skelter by muzzle flashes and the kind of uncanny lightning that brings monsters to life. Glowing busts of strangers hovered like phantoms in midair, revealing faces that were at turns frantic and eerily serene. To enter such a place was like crossing into some exotic, unmapped circle of Hell, an electrified cathedral of chaos attended by gibbering sugar-junkies, dazed potheads and hypnotized thralls.

Our goal in those days was mainly to rack up points, as much a competition against other gamers as it was against the programmers themselves. While later cabinets featured head-to-head combat, the older form of battle was largely against faceless villains, who existed only as initials and acronyms printed on a screen. I remember those weirdly tense moments before firing up a beloved game, waiting for its attract mode to display the leaderboard and worried that “ASS” had somehow reclaimed the hi-score in my absence.

Even absurd competitions breed excellence, though, and there were certain games I came to master. For instance, I ruthlessly mowed down the mechanized scum of Robotron: 2084, and taught the literally lethal chatbots of Berserk the meaning of pain.

Looking back on that now, it seems oddly appropriate. Our lives are stories, after all, and every character deserves a good origin myth.

Where We Are

Speaking of stories, that’s mainly what the video gaming industry has become: a storytelling-medium.

Not all of it, of course; the bulk of phone-based games seem to indicate at least an echo of the ancient ways, for instance, if not a full-on revival of them. But the so-called “Triple-A” titles published by larger companies have mostly adopted the story-driven model of gaming. The primary goals of such publishers are now immersion and escape, via offering their players the lead role in a cinematic narrative.

To provide escape routes from this mundane world into a more “exciting” and “meaningful” virtual one was once purely the job of the fantasy novelist. In the best of those works, the lines between input and output often blur. While we can’t participate in a literary world with any real agency, we still play a vital role in its construction, as our imaginations cast the characters, dress the sets, conjure voices to speak the dialogue as we read it.

For around three decades now, the storytelling of video games has been much more straightforward in its structure and participatory depth. As the “reader” your imagination is outsourced to a set of mechanical processes, which are then refracted at you through secondary sources of sound and light. The tradeoff is that you’re not merely an agent within this sort of narrative, but its main character and primary focus.

That said, most story-games have thus far been more or less told “on rails”, in the sense that its authors maintain control of the overall arc. Because of this, your agency within them is somewhat illusory, even in those games which promise otherwise. While you’re free to define how the action and/or dialogue plays out within a particular scene, you cannot kidnap the larger plot, or cause it to veer wildly from the author’s original intent. The duel with Laertes will always the final boss battle of Hamlet, in other words, no matter which path you take to reach it.

There have of course been experiments in enhanced story control, the Elder Scrolls, Mass Effect and Cyberpunk 2077 games/series being just a few of the more recent and notable examples. In addition to offering players some limited plot-branching powers, the “open world” format of these games also adds new elements of tension to certain choices a player makes.

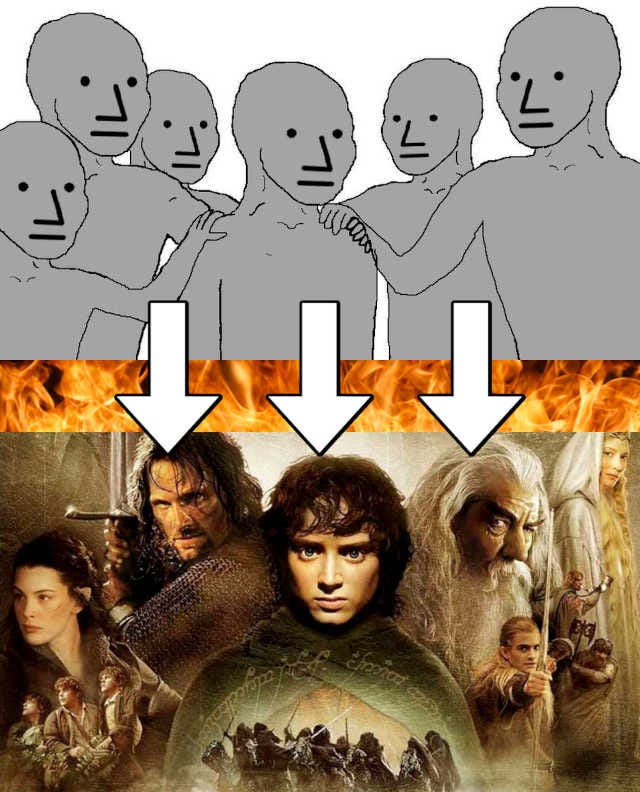

In the somewhat more venerable format of MMORPGs, the craftmanship of a pre-written story was sacrificed for the more organic, player-driven evolution of the world. For a little while, it seemed like this style of gameplay would be ascendant, fulfilling the promise of “virtual reality” from decades past. Conversing with NPCs in these games was of far less importance than your interactions with other human players, wherein most of the storytelling was actually accomplished. Players chatted via text and voice apps, formed clans and tribes, swore oaths of loyalty and revenge to friends and bitter rivals. They became functionally similar to a bunch of improv actors, or kids fighting imaginary dragons in a sandbox.

By contrast, the solo story-gamers of the current era prefer narratives that are more intricately and intentionally plotted behind the scenes, and which can surprise them in the same way a good film or novel can. Increasingly, they also desire the kind of persistence that’s generally absent from MMOs, where player avatars merely respawn after death. In other words, the players of story-driven games desire dramatic tension and stakes. The lack of persistent change within a game’s world renders such stakes impossible, and too much control over the story can deflate dramatic tension fast.1

To compare it to the tabletop role-playing format, it would be like playing Dungeons & Dragons without a Dungeon Master to prepare the story’s setting, characters and key plot threads, reveal secrets in dramatic fashion, and generally keep the players from floating off into pure, anarchic madness with their choices. I’ve heard the best DMs are the ones who walk this exceedingly fine line, becoming nimble enough to surprise their players in ways that were both planned in advance or improvised on-the-fly.

In the video game version of this, the analog to the DM is the publisher’s creative team. Much like a major Hollywood studio production, these teams tend to be large and multifaceted, and fulfill many of the same filmmaking roles. In addition to the 3D artists who contrive and render the visuals, they include story editors, scriptwriters, actors and directors, musical composers, sound engineers, etc. Even someone akin to a cinematographer is often present, to oversee a game’s lighting and color-grading.

They are massive enterprises, in other words: creative and technical juggernauts that require great sums of time and money in order to construct their immersive works of interactive fiction. The story-driven games of today often include dizzying layers of alternative dialogue, multiple branching story paths and customization options that would have been unthinkable to a young Magnus-in-training, slaughtering 8-bit robots in those caves long ago.

And it’s all about to go away forever.

I present to you the games of the future: coming soon to a home-theater, VR helmet or haptic-feedback unitard near you.

The Soup-Pot Method

“Double, double toil and trouble: Fire burn, and cauldron bubble.”

— Macbeth: IV.i 10-19;

The new standard of game design will be something I call “soup-pot” development.

In this model, the pot could be thought of as a “blank” game, optimized for storytelling. It includes functional templates for all the typical action/RPG elements, including NPCs, items & inventories, crafting systems, major plot developments, movement and combat systems, etc. For a visual analogy, you can imagine the world of this proto-game as a limitless flat plane, populated by blobs of translucent clay. It is minimally playable in its current state, but there is nothing of interest to see or do in its content-free world.

The flame beneath this pot is a bundle of generators, transformers and filtering processes, trained to add form and detail to the blank game. Similar to GPT, new data passes through many layers of analyzation and inferential extrapolation, and ML techniques are employed to refine the results. Via this process, a formless Platonic blob gains the shape of a snowy mountain, a sprawling city, a plumber named Joe who dreams of one day becoming a professional ballroom dancer.

Both the pot and its heating mechanism will be licensed out to designers by one or more industry leaders in their respective fields. These new game designers won’t be required to understand how any of these systems work, and may know nothing of the cooking process at all. Instead, their primary function will be similar to chefs tossing ingredients into the pot.

If operating as teams, their organizational structures will be much smaller and more loosely defined than they are now, with the vast majority of the current industry’s technical jobs having been rendered obsolete. In some cases, active development roles may be reduced to only a handful of cooks, or even crowd-sourced by prospective buyers/players themselves.

Q. So what are the ingredients that gets tossed into these pots?

A. Every kind of media imaginable.

Novels and short stories; character bios and vehicular specs; concept art and photography, music samples, clips from popular shows and films; snippets of important dialogue or scenes; narrative flowcharts; historical documents; thematic poetry; bullet lists and random notes, of the kind once scratched on cocktail napkins.

All of this and more will be cast into the soup-pot’s bubbling broth, to be stewed by the flame’s spectral algorithms and statistical inference methods. Even other games will be fed in, either as general design directions or to copy certain elements of them wholesale. As the heating process commences, all of these ingredients will be extrapolated into recognizable shapes, sounds and control schemas.

What emerges from the pot will be a stew that is also a game that is also a story that is also a world that is also a dream that is also, and ultimately, a nightmare.

But before I describe the form of this ultimate gaming nightmare, let’s take a moment to give the dreamers their due.

The Dream

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

— Arthur C. Clarke

In the very near future, game designers will primarily be artists, and their cybernetically-authored games will drive an artistic movement unlike any before.

The soup-pot model will render all but these neo-creative chefs obsolete. The current technical, financial and temporal barriers to contemporary game publishing will be smashed to pieces upon their arrival, as will the necessary evils of the managerial and bureaucratic structures that support it. With the flame automating the lion’s share of the engineering, 3D modelling, animation and other dreary, time-gobbling tasks, a design team’s focus will be entirely directed towards the realization of the vision itself.

These new artists will still want to tell stories, of course, because that is what human beings both do and are. But unlike the storytellers of the past, they need not structure their tales in a particular order or format. A more plot-centric writer may train his game to push forth certain storylines or twists with all its might, forcing the player to push back at least as hard to avoid experiencing all his carefully contrived setups and payoffs. But many teams will merely provide the soup-pot with some general guidance, and only the most skeletal forms of plot and story. Instead, they will concentrate their work on establishing the setting and tone of the world in which the game will take place.

Other authors on will spend most of their time lovingly crafting the game’s supporting characters, supplying them not only with physical descriptions and elaborate backstories, but with complex personality profiles which will inform everything they say and do. In addition to their knowledge of the game’s world, these new NPCs will be assigned hidden motives and desires, hobbies and pet peeves, hopes, dreams and a multitude of other interior qualities that render them as unique and richly detailed individuals. Better yet, this can all be accomplished through clever prompt engineering:

Lizabell Lionsong is a petite 24 year-old half-elf and druidic illusionist, who looks like a cross between Elizabeth Olsen and Emma Stone. While she appears to dress in elaborate costumes that imitate vines, flowers and other woodsy forms, such outfits are strictly illusory, since she can only cast spells in the nude.

Lizabell has quick wit, a saucy sense of humor, a penchant for playing pranks and a notorious taste for wine that she acquired during her years of exile to the cities of Man. She also has a knack for getting herself and her friends into trouble, usually when one of her pranks or spells goes horribly awry…

With just a few pages of description of this sort, the flame will cook up an NPC that more or less resembles this character in looks and personality. After testing and creative review, she can be further refined with additional prompt engineering. Via this process, the ML framework will eventually adapt to a given chef so well that the refinement step itself will become mostly unnecessary; the flame will know exactly what its artist wants to cook.

Instead of executing scripted commands based on event flags and relationship metrics, soup-pot NPCs will initially act according to their creative writing prompts, with their behavior adapting organically to player interactions, plot events and other story developments. Depending on how you treat them, they may challenge you to duels; fall in an out of love with you; hit you up for cash when they’re broke; swear eternal allegiance to your cause; betray you at the worst possible moment because of something cruel you said to them long ago. In other words, they will act as literary characters who’ve been set loose from the page.

All of their dialogue will be generated during runtime by an NLP, and vocalized by a synthetic speech engine that can be calibrated to simulate any number of voices. As such, there will no longer be a need for teams of dedicated writers, cranking out vast tracts of flavor text and mind-bendingly complicated dialogue trees to account for changes in knowledge or emotion. What dialogue is supplied in advance will merely be demonstrative of a character’s general personality and tone.

If the NPC is based on a human actor, sample lines may be read into the pot as transformation targets, along with biometrics that measure breathing patterns and other vocal artifacts for deeper visual and auditory mimicry. But overall, the need for actors to be physically present will be greatly diminished. While some in-person participation may be initially required for design targeting, the bulk of design and implementation will largely be drawn from his or her previous games and films.

Of course, the greater degree of a performer’s direct involvement in a given project, the more accurate and believable their digital doppelgangers will become. Big budget projects will therefore still exist which operate somewhat similarly to the current “filmmaking” design model. However, indie teams will also be able to use the likenesses of some licensable actors, either as general guides for 3D models or as fully deepfaked members of their virtual casts.

Teams will also continue to include a variety of experienced and talented visual artists, including painters, illustrators, sculptors, costumers, propmakers, architects and more. Their artistic visions for a project will no longer be limited by budgets, or vandalized by a bunch of mediocre corpo-critters who like to fancy themselves as “being creative, too.”

In the realms of science fiction, horror and fantasy, the results will be staggering. Players will visit vast floating cities, jungles filled with alien flora and fauna, lunar mining settlements patrolled by towering mechs. You will come face-to-face with terrifying monsters of every shape and size, pilot whimsical steampunk vehicles across sprawling deserts, and starships into the deepest reaches of space. You will attend lavish ballroom parties to dance with Hindu deities, scour wastelands and ghost towns for meagre resources, investigate murders in an alternate-universe 19th century London, where vampires and werewolves rule the night.

There will of course be many strictly derivative works as well, pulled directly from works of popular fiction. The worlds of Harry Potter, Star Wars, A Song of Ice and Fire and more will be diligently and painstakingly recreated from their respective media. In some cases, the game will seem to open a portal directly into a particular film or show, where you might take on the role of one of the principals, or Mary-Sue your way into the plot as a brand new character.

Bizarre boutique projects will also emerge, in which hipsters invent new forms of surrealist art. They will reset an episode of Laverne and Shirley in a post-apocalyptic hellscape, crank out batshit worlds composed entirely of cat memes, tell tales of anthropomorphic banjos who chart the cosmos.

Some story-games will drive sensory realism to its very limits. Visual representations of people and places within such projects will approach the photorealistic detail of HD films, as will their omnidirectional sound. Enhanced controls like force-feedback webbing, haptic gloves and similar garments will mimic touch and pressure. If helmeted, the differences between the game and our living world will appear to be quite slim, and some players may hardly notice them at all.

Customization tools for these games/worlds will likewise be astonishingly powerful. While some will be integrated by the game’s publishers, eventually we will see more intricate packages, sold separately by third parties. However detailed you think the options of current gen games are, they will look like crude toys compared to the soup-pot version.

Those users who are especially picky and intrepid will essentially become the soup’s final chef. The most powerful of these tools will grant them the ability to make in-depth homebrews which alter major aspects of the story or world in godlike ways. They will recast various roles with their favorite actors, or even with people from their personal lives. They will change the lengths of days and weather patterns, add new flora and fauna, turn heroes into villains and vice-versa, repaint the color of the sky.

As a result, new communities of passionate modders will flower into existence almost overnight, with the most popular ones spawning secondary markets for their variants. They will convert gritty, violent action games into screwball comedies, imbue well-known characters with new personalities and motives, expand existing stories into detailed spin-offs, sequels and reboots.

In both these primary and secondary markets, the results of early experiments will vary widely in their quality, as designers race to find and hone the best formulas and practices. But gradually a bell curve will emerge, the mean of which will be a somewhat unified approach to story-game design that solves the riddle of this current generation. This new game template will strike the perfect balance between authorship and agency, including just enough choice, tension, persistence and surprise to keep its player constantly engaged and wanting more.

The result will be a seismic cultural shift not just in gaming, but in the world at large. For example, as more and more people gain access to these technologies and play these games, they will become happier and less anxious about achieving and maintaining professional success or social status.

As a result, the world will begin to heal itself. There will be a significant drop in violent crime, fewer drug addicts and gamblers, a sharp decline in car wrecks and suicides. Riots and politics will become a thing of the past. Who has time to riot, when you’re busy saving your town from a demonic horde, or ruling an ancient kingdom with an iron fist, or trying to flirt up Natalie Portman’s latest deepfake avatar in a nightclub on Mars?

The answer is you won’t have time for any of it. That’s because the so-called “story of your life" will branch off into a hydra of far more exciting, intriguing and meaningful lives, to be revisited or rebooted whenever the mood strikes.

You will inhabit these stories as fully as you would the most lucid of dreams. But unlike an actual dream, the machine version will never fade or falter, never thrust you back into the cold light of a cold world. Our new games will be the kind of stories that never end, and the dreams we’ll never want to wake up from.

Or will they?

🤔

Obviously I have more to say. But I’m trying to keep these posts to a reasonable length, so I’ll conclude this little thought experiment in Part Two.

In the meantime, feel free to comment here. But bear in mind that the “dream” I’ve outlined above isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, in my humble opinion.

P.S. If you found any of this valuable (and can spare any change), consider dropping a tip in the cup for ya boy. I’ll try to figure out something I can give you back. Thanks in advance.

Unironically, the same might be said of life itself.

Well, the WEF's Yuval Harari says it'll likely be a combination of drugs and video games that will be used to placate the "useless people" once the utopian dream of owning nothing, having no privacy, and nonetheless being happy is realized. I guess the powers that be will turn their attention to developing newer and better narcotics and video games once they get done dismantling everything in our civilization that they can't fully control. Looking forward to your followup pieces on this subject!

On a different note, old school arcades were a different variety of, rather than a replacement for, in-person socializing. I guess they're not what Harari has in mind, though, for all us "useless people."

This is sounding more and more like Guantanamo Bay on acid. What you're describing is effectively the Matrix, which I feel is the goal of the transhumanist bio-digital convergence, or at least part of their goal.