Spook Central (Part 2)

Artificial intelligence, stochastic resonance and the Internet of Things are making the unseen worlds more visible. Now what?

In part one, I described the current state of Internet’s datasphere, and posited its encoded signal traffic as a medium for “paranormal” agents to gain control over material. But before we explore this idea in more depth, let’s take a step back and have a fresh look at how we got here.

The Server Tower of Babel

What are the roots of the Internet?

Was it a top secret military-industrial project? A centuries-old central banking scheme? The handiwork of occult magicians and spiritual con-artists?

When you look at the question through the lens of 6GW, the answer is “All of the above, and more.”

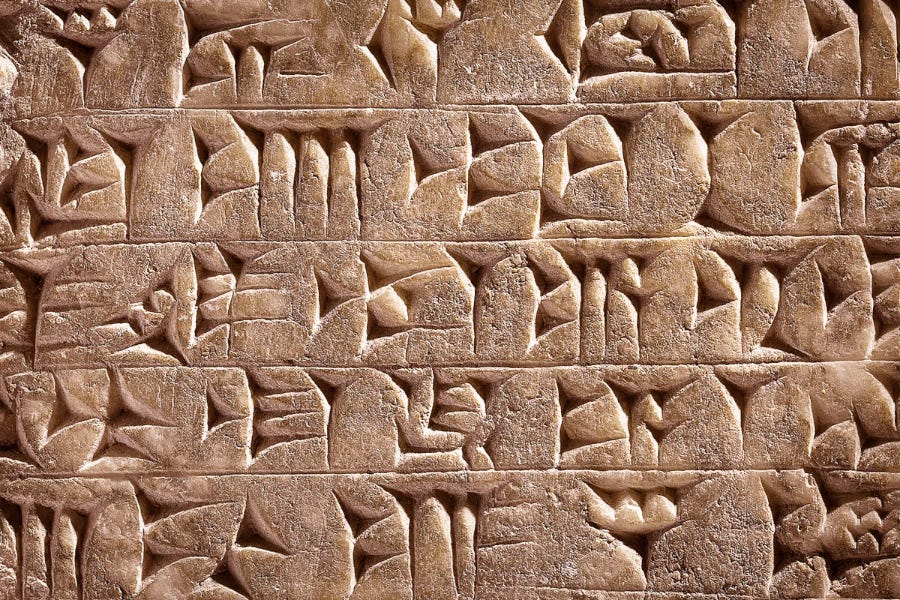

But the story of the Internet’s arrival is far older and more complicated than the specific engineers and tools that gave rise to it. It stretches back to the earliest development of written language, or even of nonrepresentational pictures and symbolic glyphs. This is when we first began transcoding between signals of sound, light and other sensory phenomenon, converting them into compressed formats called words. A word is a shortcut, after all; an encoded signal which decrypts and decompresses into something much larger and more complex in the mind.

For instance, consider all the images, sounds, smells and haptic sensations that a simple three-letter word like “dog” decodes to when you read it. You can recreate not just a dog or many dogs, but something akin to a Platonic shape or template of the dog taxa, from which you can generate new dogs in your imagination.

These new dogs don’t even need to conform precisely to the known patterns or rational limits. You can imagine cybernetic dogs, Martian dogs, fifty-headed dogs that guard the gates of Hades, etc. I mentioned in the last article that the “language of Mother Nature” is frank, and that a zebra couldn’t suddenly “decompress into a herd of wooly mammoths.” But such an event is certainly possible in your imagination. And particularly in an artist’s imagination, where a dog might decrypt into a cosmic horror of protean anatomies.

In addition to these innumerable data points and design possibilities, the decompressed word may also conjure the swirling memories of a specific dog that you owned, including all the emotional content of that relationship. It turns out the animal’s entire life was contained in those three letters, from his puppy training days to those last moments at the vet, when you had to put ol’ Sparky down.

In short: Words contain worlds.

Now, take a moment to consider that this process of compression-decompression is something that each one of us is doing all day, everyday, decoding whole worlds at speeds and volumes that are so immense as to be entirely immeasurable. This process isn’t limited to our reading, either. Unless we’re hermits living in a cave, we’ll translate spoken words too, as well as non-verbal transmissions of all kinds. In his final days, you recall the miserable pleading in Sparky’s eyes was almost as palpable as human words. That dog couldn’t speak, but he sure as hell could signal.

Here’s an interesting question though: Could Sparky send false signals? Could the creature not just send and receive, but deceive? In other words, can a dog encode a signal that is intended to be decoded incompletely or incorrectly on the other end?

The jury’s out on that one. Unfortunately, it mostly seems to be comprised of deceivers themselves, including self-deceivers. These are the contemporary crop of behaviorists, psychologists, evolutionary biologists, and other pseudoscientific grandkids of that Great Mistake we misnamed The Enlightenment. That’s around the time the West began to mistake deceptive signals for truths at an industrial scale, and lose our own spiritual coherence in the process.

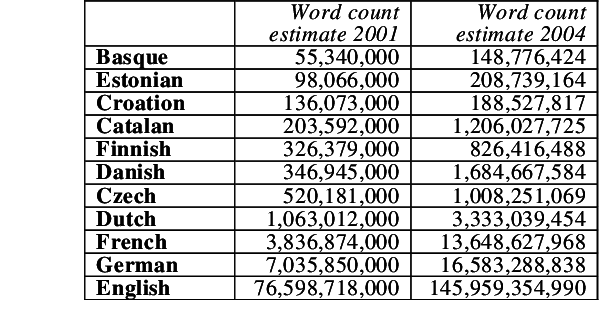

Not coincidentally, this explosion of deception and spiritual decay correlates well with the growth of legible words. This is especially the case with the English language, and especially during the rise of the consumer Internet.

In 2010, Harvard linguists Drs. Jean-Baptiste Michel and Erez Lieberman Aiden (in partnership with Google, Encyclopedia Britannica and American Heritage Dictionary), documented this alarming trendline using the latest in data analytics techniques.1

The language has grown by more than 70 per cent since 1950 …. The previous half century it only grew by 10 per cent…. {it is currently increasing} by 8,500 words a year.

We could look at this trendline and say:

Well, of course!

Greater technical specialization requires the invention of more language shortcuts. They function as foundations for ever more complex frameworks to be built upon.

But a big reason for Michel and Aiden’s unbelievable findings wasn’t due to technical need per se, but rather the sharp rise in what they termed “dark matter” lexica; slang, jargon, loanwords, neologisms and other strings that fell into common usage despite existing outside the standard registry of dictionary definitions. They determined that 52 percent of the English lexicon now consisted of these non-standard words.

A slim majority, perhaps. But when you consider this trendline alongside others (declining literacy, mass migrations, etc) it’ll be a wonder if anyone will be able to understand what anyone else is saying, twenty years from now.

So in addition to enduring the new (packet) Flood, we could be witnessing the final build cycle of the new (techno) Babel, shortly before it all comes crashing down.

The error that triggered this particular doom loop is a (perhaps intentional) misunderstanding about complexity. More words do not translate to more meaning, and in fact can eventually devolve into babble. The same can be said of devising ever more complex words and concepts. Each time we add complexity to any system, we pay for it with added fragility.

Normal, honest people and truth-seekers understand this, which is why words like “egghead” and “snob” are still very useful. Some people will employ a fancy, voluble, overcomplicated vocabulary as part of a status game they are playing, or to cover up their insecurities, or in pursuit of some other pathetic ego-driven goal. Whether consciously or subconsciously, we recognize this pretentious use of language as a form of deception.

If the deceptions and deceivers are harmless enough, we can laugh them off. If their word-game seems at all malicious, we can crack the egg or prick the balloon with a few choice words of our own. Comedy is especially useful for this task; people who try to meta-game language rarely have a sense of humor about themselves. I would advise expanding your own vocabulary as well, if only as a defensive measure against gibberish. It will also help you translate instantly from egg to omelet, in which case comedy may ensue.

But there is another level of encoded word sorcery which isn’t only malicious, but can rise to the level of existential threat if left unchecked. Some language developers will intentionally contrive code for the purpose of demolishing objective meaning altogether. Others will employ esoteric codes in plain sight, to send signals that are kept secret from all minds but their fellow agents. These sorcerers will even cooperate in these secret projects, with the shared purpose of world domination, freedom from moral constraint, and godlike power.

In other words, language can be used as an occult signaling technology. The codes partially decrypt and decompress into bodies that, if properly decoded by their exoteric targets, might get the coders locked up in prison (or worse). That’s because the games these people play don’t only involve the commission of mundane crimes. They include the sort of crimes that might even shock the modern conscience, as sadly diminished and overly “tolerant” as that’s become.

But no amount of symbolic graffiti or ciphers can accomplish an evil end per se. The tower of Babel must be built floor by floor. At each new rung, the exoteric inhabitants must be nudged and groomed to accept what was broadly unacceptable at the rung below. It’s not an easy feat, particularly when you have co-conspirators and orcs running around and smashing the place up on a regular basis. You need to start with a foundation solid enough to support all of the hijinks and lab explosions and whatnot.

So what was that “solid” foundation, that allows for structured chaos?

How is it, for instance, that the following signal is allowed to be broadcast, without its various enablers and authors being dragged into courts, or onto gallows?

Man of the Margins

At the most basic level, a signal requires a transmitter (or emitter), a transmission (or emission) and a receiver. The signaling structures and transfer mediums can vary in material, but those are the requisite elements for a signal to properly be said to even potentially exist. But the signal doesn’t gain coherence without an observer to measure it (or, in John Wheeler’s version, to ask questions).

Our own biological structures include all of the requisite signaling equipment, and then some. But humans, as we know, aren’t typically satisfied with the basic loadout. So we’re always contriving new tools and techne that extend and enhance various functions. This hammer enhances my fist, this megaphone extends my voice, the Subaru hatchback extends and enhances my feet, legs, lung capacity, etc. We even design tools to extend and enhance our mental capacities, such as runes, scrolls, books, calculators, Palm Pilots and search engines.

We think of these latter tools in terms of hardware/software relationships, which some of us will mistake as analogous to the body/mind problem. For example, I’ve mentioned before that my old laptop — the one I used to design the Harm Assistant — seems to be caught in a downward spiral of progressive memory exception errors. A more poetic way to put it might be that the machine’s “brain” is slowly eating itself. But we toy with that kind of bad poetry at our peril, because it wildly distorts our picture of reality.

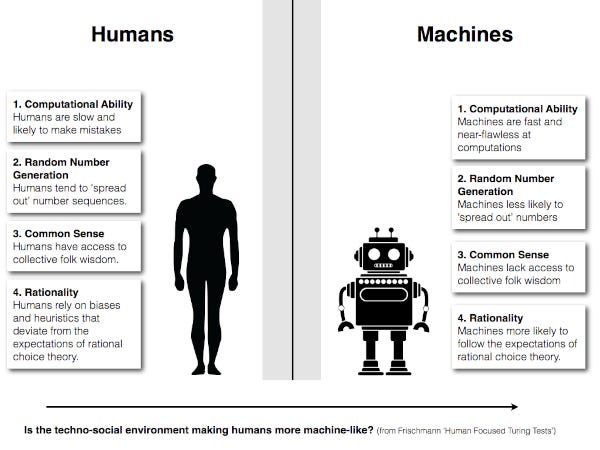

The reason we often use biological metaphors to describe our gadgets these days — and, more disturbingly, gadget metaphors to describe ourselves — has deep roots in the philosophy of science. When it comes to who-or-what did the most damage, there are many strong candidates. But I personally trace the problem back to René Descartes’ theory of automata.

I first encountered this error in a linguistics course I took many years ago, which might as well have been called Artificial Intelligence 101.2 Most of the material was Chomsky, along with a smattering of Baudrillard and a few other 20th century French neuropaths. We were also required to pore through reams of Alan Turing’s experimental “work”, which struck me as laughably insane. I was not a popular voice in those recitations.

But our first assignment — the gateway drug — was René Descartes’ musings on the difference between Man and machine. In this case, the machine in question might’ve been ol’ Sparky, happily chomping on his favorite bone in the corner. The fault line he carved was between kinesis that was purely reactive or automatic (e.g. heart regulation, blood flow, muscular reflexes) and that which required cogitation, concentration and strategic intent (e.g. all complex human actions, communications and endeavors, according to his standard). The irony here was that in trying to place further distance between Man and Beast, he accidentally sent both on the dark forked path to the Machine:

From René Descartes’ Réponse de M. Descartes a M. Morus, 1649 (emphasis mine):

“But as regards the souls of beasts, although this is not the place for considering them, and though, without a general exposition of physics, I can say no more on this subject than I have already said in the fifth part of my Treatise on Method; yet, I will further state, here, that it appears to me to be a very remarkable circumstance that no movement can take place, either in the bodies of beasts, or even in our own, if these bodies have not in themselves all the organs and instruments by means of which the very same movements would be accomplished in a machine. So that, even in us, the spirit, or the soul, does not directly move the limbs, but only determines the course of that very subtle liquid which is called the animal spirits, which, running continually from the heart by the brain into the muscles, is the cause of all the movements of our limbs, and often may cause many different motions, one as easily as the other.

"And it does not even always exert this determination; for among the movements which take place in us, there are many which do not depend on the mind at all, such as the beating of the heart, the digestion of food, the nutrition, the respiration of those who sleep; and even in those who are awake, walking, singing, and other similar actions, when they are performed without the mind thinking about them. And, when one who falls from a height throws his hands forward to save his head, it is in virtue of no ratiocination that he performs this action; it does not depend upon his mind, but takes place merely because his senses being affected by the present danger, some change arises in his brain which determines the animal spirits to pass thence into the nerves, in such a manner as is required to produce this motion, in the same way as in a machine, and without the mind being able to hinder it. Now since we observe this in ourselves, why should we be so much astonished if the light reflected from the body of a wolf into the eye of a sheep has the same force to excite in it the motion of flight?

Translation from Egghead:

Animals don’t think.

This was a monumentally stupid error. But it was also one rooted in a certain form of spiritual blindness that looks righteous on the surface. In formulating this excessive distinction, he believed he was elevating Man to his proper position in the order of Creation, as the imago dei and child of God. He also likely had little to no conception of future implications, such as industrial automation, digital computing, the development of machine learning applications, or the insane delusions of those who chase the dragon of AGI. For him, a “machine” still meant something more akin to normal human markets and flourishing, even as metaphor.

His big blunder was that even the most casual observation of animals will reveal thought and intent, including strategic intent based on predictions. It will even reveal the communication of such thoughts and intents, through both acoustic and non-acoustic signals (e.g. birdsongs, postural changes, grooming, mating and combat rituals, etc). Although these animal signals and the minds that transceive them aren’t anywhere as sophisticated as our own, they very obviously exist. In that sense, you could also call Descartes’ mistake a matter of championing map over territory, abstraction over incarnation, ivory tower theory over on-the-ground reality.

But one symptom of looking at reality from the tower resident’s flattened, monocular perspective is a sneaky hubris, which quietly renders even the most obvious data illegible. This happens in the other direction as well; if your material eye is blind, you will become infected by a spiritual hubris that also detaches you from reality, including its most glaringly obvious aspects. I suspect that’s how malevolent cult leaders, gurus and other religious maniacs are born. That may also be the origin of both animal and human sacrifice, as “death” in the eyes of the materially blind loses its teeth.

But Descartes was also a man of his times. Despite his professed religious beliefs, the order of the day was to close or squint that spiritual eye, so the investigators could more clearly see the “lights” of the material world and make progress towards them. That was what Descartes assumed he was doing, in advancing his theory of animals-as-machines. But the unintended consequence was to kickoff our descent down a slippery slope I call the Marginal Man Effect.

The slope of demystification is similar to the God of the Gaps; as the life sciences proceeded to reduce biological structure and experimentation to ever smaller and (theoretically) automated, unconscious components and processes, the line between Man and machine could be redrawn ever closer to the latter, until it disappears entirely. Instead of describing Man in purely animalistic terms (which Descartes rightly feared), we would eventually talk about all lifeforms as machines; a collection of components, to be poked, prodded, dissected and otherwise experimented on without moral compunction.

That’s how we come to find lunatics like Turing, Chomsky, Dawkins, and Fauci ascending to the heights of social influence and material power. Amusingly, it’s also the reason most of these men were eventually defenestrated by their former friends and cheerleaders, in accordance with the merciless, mechanical, Luciferian worldview they helped shape and promote.3

Our current crop of institutional Charlie Ponzis and Robespierres tend to have cataracts in both eyes, so they never see it coming. But their replacements are never better, and are usually significantly worse due to the side effects of the Neo Flood. They don’t dare try to correct the original errors, since that would require a multigenerational bonfire of bogus research papers, inflated reputations and all the social and financial privileges they confer. Instead, they dig their heels in even deeper, and begin to pump out signals so byzantine, glib or illegibly vague that they also become indistinguishable from noise, even when decrypted at the receiver nodes. Their statements are ciphers nested in ciphers, lies wrapped in lies, in support of conceptual frameworks so laughable they make Alan Turing look like Marcus Aurelius.

For many human receivers, the result is a kind of hypnosis. If you’ve ever heard a magical incantation, they also tend to be larded with gibberish, loanwords, fancy neologisms, and other word-like sounds that don’t easily decompress in the listener’s mind the way that “cat” or “dog” might. Like Babel’s own mythic structure, it is the stacking of nonsense on top of nonsense, every layer more inscrutable than the last.

The noise leaves many listeners dazed and confused, or even echoing the fancy gibberish in order to sound competent and praise-worthy. But underneath that, they probably also sense that these credentialed figures and industry captains must know what they’re talking about. The proof is in the magical devices they spin out, offering simulated worlds of hedonism, amusement and convenience for “free.” Why would you ever question the Candyman? Or the guy in the white unmarked van full of puppies?

The situation is exactly that dire.

But there’s something else happening right now, a parallel effect. Not everyone is receiving or these transmissions as intended or designed. In fact, the current trajectory of the Internet has led many to the opposite shore, where they can see and untangle truths from the most Gordian of lies.

Why is that?

Why are some people able to extract signals from the superstorm of noise?

I think there are two reasons this is happening: one material and one spiritual. When you put them together, the unseen worlds decloak before our eyes. There’s even a bunch of fancy words for the phenomenon, which some modern researchers call “stochastic resonance.”

Translation from Egghead:

The darker it gets, the better some folks can see.

To be continued…

The Cat Was Never Found is a reader-supported blog. I don’t publish much paywalled content, so your generous patronage is very much appreciated. As a reminder, a paid subscription will also grant you access to Deimos Station; the happiest place in cyberspace!

P.S. If you found any of this valuable (and can spare any change), consider dropping a tip in the cup for ya boy. It will also grant you access to my new “Posts” section on the site, which includes some special paywalled Substack content. Thanks in advance.

Michel, Aiden et al, Quantitative analysis of culture using millions of digitized books, 2011.

It actually may have been called that. I can’t remember at the moment.

Fauci has yet to fully join this defenestrated group, but give it time.

"More words do not translate to more meaning, and in fact can eventually devolve into babble."

I've been working on reading some older books from the Western canon of literature, and I am consistently impressed with the density and intricacy of the language older authors used. Beyond just the word choice, there's a follow-through and an attention paid to the meaning of each sentence and how it fits into the whole.

Conversely, a great many modern nonfiction books I've read, from within the past five years, contain a profound incoherence. For instance: John Higgs, in "William Blake vs. the World," somehow manages to argue that Blake agreed with all the concepts of modern materialist science, despite the scathing vitriol Blake expressed, throughout his life, for the entire project of the Enlightenment.

The evolution of language as it bloats with slang is as fascinating as it is disturbing. I look at the kind of slang that defined my generation in our youth, and it was, for the most part, rather shallow and easy to comprehend. Looking at the youth of today, I see that not only is their jargon and cant much more expansive than what I remember, but it changes with such speed that it's almost difficult to grasp. It's easy to laugh at bullshit like "skibidi toilet" and "rizz" and "gyatt" and the fact that these words cycle out of the zeitgeist almost as fast as they get into it, but I do think it portends a worrying trend. I know people who say, "I have no idea what my six year old is saying", and laugh about it. And, again - I get why. But if this is how fast it's happening now, enabled by short-form, rapid-fire content generators like TikTok and the like, I can easily see a future where we reach a peak where communication between generations is almost impossible without a translator. I could just be worried about nothing, I'll admit, but it's an interesting thought experiment if nothing else.