So times were pleasant for the people there Until finally one, a fiend out of Hell, Began to work his evil in the world. Grendel was the name of this grim demon Haunting the marches, marauding round the heath And the desolate fens; he had dwelt for a time In misery among the banished monsters, Cain’s clan, whom the creator had outlawed And condemned as outcasts. For the killing of Abel The Eternal Lord had exacted a price: Cain got no good from committing that murder Because the Almighty made him anathema And out of the curse of his exile there sprang Ogres and elves and evil phantoms And the giants too who strove with God Time and again until He gave them their final reward. — Excerpt from "Beowulf" (Translated by Seamus Heaney, 1999)

I have a complicated relationship with the work of Cormac McCarthy.

His voice is one I both struggle with and savor, in the way a proud laborer savors his sweat. Reading works such as “Blood Meridian” and “The Road” at times felt like a wrestling match against an opponent twice my size. But again: in struggle, glory.

So when a friend insisted that I read a fifty-year-old novel by the man, I was both glad to take him up on it, and at the same time wary of what I was getting myself into. He warned me not to read a single thing about the book in advance. It was only afterwards I would learn that “Child of God” — like most of McCarthy’s early work — was a commercial and critical flop on first printing. But like so many re-releases of misunderstood books and films, its new critics all gushed with praise.

And yet, they still wildly misunderstood it.

There are many reasons for their fresh-yet-still blundered takes, most of which loop straight back to the mistakes of the postmodernism that brewed them. Not being educated in the art of myth (or in much of anything else pertaining to the spiritual world), the tale itself seems to fall like water through their outstretched fingers, which are then licked for the slightest of nourishments.

Warning: it will be impossible to discuss this book without spoiling its plot. There isn’t much of that anyway until the book is halfway finished. But when it gets going, the author springs a number of surprises on his reader that are best consumed raw. On the other hand, the plot is of little significance; if you know what happens in the epic of Beowulf, then you know what happens in Child of God.

For those who prefer to read it first then return for discussion, here is my review in brief:

I unequivocally recommend this book. If it’s your first encounter with McCarthy’s style, your head will likely spin for the first twenty pages or so. Remain calm. Let the language flow, and gradually work its spell upon you. If you’re already a fan — or even a harsh critic — of his later work, try to avoid comparing it with those. Finally, if you’ve already read this book long ago, consider revisiting it. You might find, as I did, that it’s not only a work of genius, but a mythopoetic portrait of our current age, and its crisis of spiritual ruin.

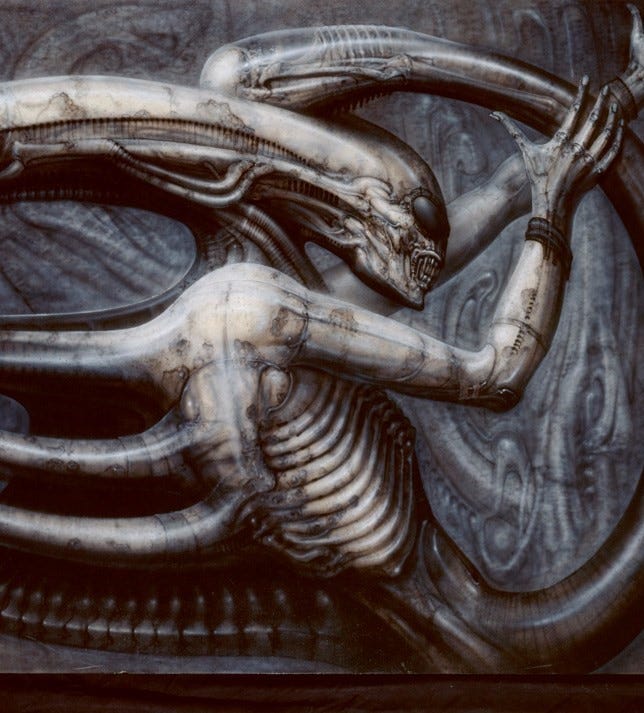

I’ve always been fascinated by monsters, and particularly those of the so-called Cain Tradition. These are the singular monsters of exile, those rimwalkers and wasteland wanderers who haunt the deep places. Due to some unholy crime or condition of being, they have been detached from the body of Man and his societies. They are also creatures who have been visibly “marked” in some way, in order for mankind to better recognize them and enforce their banishment.

The monster’s mark could be anything from mere ugliness or deformity to an alien shape that’s only vaguely humanoid in form. It could also reflect a more subtle ethereal strangeness of presentation, like the anachronistic dress and manner of Dracula in his most humanoid disguise. To be marked in such a way is considered a punishment of God, hence the tracing of the lineage to Cain the kin-slayer.

Perhaps the oldest version of this creature that still prowls our imagination is Frankenstein’s monster. Even though its anatomy was mostly scavenged from human corpses (readers often forget about those plundered abattoirs), no one would ever confuse the monster for a human. The same could be said of the monster’s mind, which, though quite powerful, (something also forgotten in pop cults) seemed incapable of warmth, mercy, forgiveness or remorse. It was not so much a case of the father’s sins being visited onto the child, but rather that the child was the demonic manifestation of the father’s crimes — and, in particular, his sin of hubristic pride, from which all other deadly sins descend. In trying to usurp his Creator, Frankenstein visits destruction upon himself and those he loves. The lonesome, exiled monster is merely a physical agent of that destruction.

For modern peoples — or, at least, more modern than Shelley and Stoker — the tale of such a monster is often twisted into one of tragedy and recrimination. Tragedy, because the monster is depicted as the blameless victim of his condition. Recrimination, because the blood libel punishment of Cain’s offspring is seen as unjust. Or rather, God’s backward and moronic followers are unjust, because for these authors and critics God doesn’t exist. So in these modern retellings, the monster is more a heroic outcast and existential martyr who sees the world as it is (or as it should be). His banishers meanwhile are mostly hypocritical liars, who punish the wretched outsider to preserve their unearned dominance and privilege.

Tales told this way invert the original legend’s principals and themes — some might say in revolutionary, if not full-blown Luciferian ways. Perhaps there’s no better illustration of this genre than John Gardner’s Grendel. Just like Child of God, the book was printed during the moral and political upheavals of 1971. I suppose one might say that Beowulf was in the air that year, finding its way onto minds and pages in different forms.

I first encountered Grendel as a teenager in the 90’s, by which time anarchy was just another mass consumer brand, rebellion a tongue-piercing or “tribal” tattoo away. Within its slim pages, the famed monster of of early English literature is transformed into the story’s narrator and tragic antihero. Gardner reintroduces us to a lonesome and sensitive being, struggling to understand his wretched condition. Unlike his mute idiot of a mother, he’s been gifted with powers of speech, and yet cursed to have no one to talk to, nothing to connect with.

By the story’s end, he is indeed transformed into the bloodthirsty, rampaging killer from the original text — but, once again, through no fault of his own. It’s rather the bigotry of Heorot that transforms him, and his raids therefore both righteous and philosophically justified. When Beowulf finally appears, he is rendered as a psychopath, and his victory over Grendel more the product of blind chance than of heroic courage and strength.

The book is packed to the gills with trendy, postmodern cruft. For example:

“I understood that the world was nothing: a mechanical chaos of casual, brute enmity on which we stupidly impose our hopes and fears. I understood that, finally and absolutely, I alone exist. All the rest, I saw, is merely what pushes me, or what I push against, blindly—as blindly as all that is not myself pushes back.”

At the time, I was spellbound by such nihilistic expressions, gobbling them down like potato chips. And because of my addiction to monsters, Grendel became one of my favorite novels. It was only with age and experience that the tale lost its luster, when I realized the ugly vandalism at work. The vandal’s target was the mythopoetic truths of Beowulf, in which monsters were properly understood to be the primary moral authors of their fates, with heroes merely serving as God’s agents helping guide them to it.

Which brings us to McCarthy’s Child of God.