Bad Good Books

Unfinished tales, monster training manuals and other works of dystopian pseudo-art.

Stanislaw Lem’s Return from the Stars is a bad good book.

By good, I mean it is “a stunning achievement,” “a tour de force,” and other marketing blurbs you’ll find tattooed on dust jackets in the airport lounge. Within its pages, we meet Hal Breggs: an astronaut whose decade-long space trip decompresses to 127 years of time dilation. Upon his return, he finds a totally unrecognizable world, peopled by a species that seems human in name only.

To impress this sense of alienation upon us, Lem kicks his polymathic skills into overdrive. The first thirty-odd pages strands the reader in the same disorienting madness as Breggs himself, at an airport that's like a nesting doll of fever dreams. His witches’ brew is a special blend of horror and comedy, where one ingredient becomes indistinguishable from the other. You’ll find yourself losing your place in the middle of an everlasting sentence, starting over, and then losing it again. By the time the prose settles into something more digestible, I imagine many copies wind up sitting dogeared on a shelf forever. You’ll get back to finishing it someday. Except, you won’t.

That makes sense, because Return from the Stars requires effort. If we stick it out, we’ll find it is loaded with immortal questions, moral quandaries, spiritual anguish, and other beautiful complexities. It is also a good book because the author genuinely loves his character, and wants us to love him too. After escaping that garish disco-labyrinth at his side, we can easily empathize with him through the rest of this talky tale. Apart from one strange car chase near the end, there isn’t a lot of “action” here. But we feel Hal’s bewilderment and heartbreak, quietly cheer for his moments of insight and resolve. We see this New Earth as he sees it, know that it is Hell disguised as Heaven. Like Winston Smith, like Guy Montag and Billy Pilgrim and the Savage and poor little Snowball, Hal Breggs sees the ugly truth buried under the mountain of pretty lies.

The story is consistent with those works of dystopian fiction in other ways, right down to its tragic ending. The hero loses. He surrenders to the monster, succumbs to its will, and is ultimately devoured. The theme is so recurrent in the genre, we might as well have named it “monster advertising.” The warning is bellowed. A hero rises. His best answer turns out to be a sigh. Eating snow in the woods, and bidding adios to the stars and the human soul alike.

It’s still a good book. They are all good books.

And they all stink.

Are they bad because they’re tragedies? No, that can’t be. Many of our truly great artworks are tragic by design. But the scale of these great tragedies is limited in scope to those individuals who become entangled in the spiderwebs of fate. In bearing witness to their lossses, we are free to understand the larger world outside those webs in other ways.

For instance, we can see the various crimes and failings that led to the hero’s ruin as the exception, not the rule. At the very least, the problems and warnings — of Hamlet, of The Brothers Karamazov, of Frankenstein — aren’t ever declared unanswerable. Many of the tragic heroes provide partial solutions, even at the cost of their own lives. And along the way, the best tragedies will give us glimpses of the higher reality. They demonstrate the pathways to forgiveness, redemption, and love, whether the heroes take those paths or not.

We must work hard to complete those great sad bridges and cross them. But, unlike the dystopias, at least the bridges aren’t revealed to be fully hallucinatory, or rigged with dynamite.

We can’t say the same for the seminal works of H.G. Wells, Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, Ray Bradbury, Kurt Vonnegut, and other famed dystopian authors, who blow the bridge to smithereens when we’re halfway across. In fact, you might call books like Brave New World and 1984 half-told stories, at best. At worst, you might call them instruction manuals for tyrants, regardless of the author’s supposed intent.

And we can only grant them so much benefit of the doubt, in that regard. Orwell was a socialist, after all, and Huxley an avid eugenicist. Because of this, their warnings often ring hollow, or sound like something else entirely when we tilt our heads just so. Who is being warned, exactly? At times, it sounds like the monster is warning its own monstrous breed. It is saying: “Here are the kinds of stupid heroes you will face, and here’s how you deal with ‘em. Muhuhahaha...”

The usual response at this point will be to pull quotes from the artists, to demonstrate how they described their own intentions. Even if we were to believe these claims — people have been known to lie strategically, after all, including to themselves — the problem is that artists often don’t know what their intentions were when they were creating the art. They are pressed for answers, and they give them in order to satisfy the hoi polloi’s demand. But the guesses they’ll make are often more clueless than the reader’s own, guided by the ego’s dream. A smarty-pants critic says something in praise of their work, and suddenly it becomes the post-hoc intent. “Yes! Yes! I meant to do that.”

But art is not like engineering. When we find a popular artwork that endures, its genius isn’t rooted in meticulous planning and measurement. The artist is more vessel than captain, and the degree to which he isn’t running the show correlates well with the beauty of his result. If he can perfectly explain it, then it likely wasn’t art to begin with. It was more likely a work of propaganda, whether or not he knew it. Even a psywar gremlin like Edward Bernays would tell you that the perfect propagandist is the one who doesn’t know his real job, and thinks he’s making something beautiful and true.

The proof is in the pudding. Just look around you.

Many will look at the past quarter century and shout, “Aha! Orwell was a prophet! He predicted all of this would happen!” Never once will they suspect that Orwell and his fellow dystopic travelers may have, in some sense, programmed it. They’ll never consider that these half-finished masterpieces groomed us to think of the monsters as invincible, and their victory inevitable.

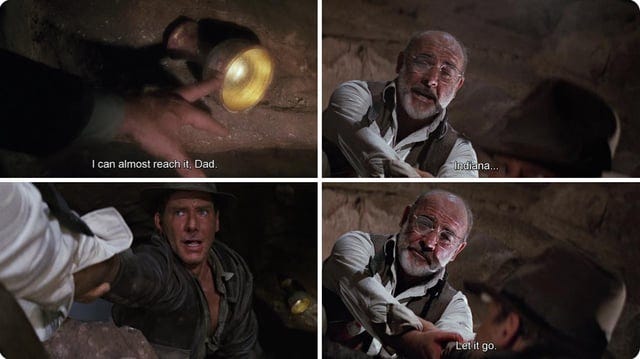

That’s the problem with telling half of The Story, which Campbell nicknamed the Monomyth. The hero is left stranded in the darkness of the katabasis, groping for a magic boon that he’ll never reach, let alone return as a gift to the world. Sometimes the boon itself is shown to be an illusion, or is lost forever down the darkest pit.

This seems to be yet another cancerous outgrowth of postmodernism more generally. When the story isn’t pure nonsense and noise, it is told halfway and then abandoned in the dark. I sometimes think Orwell would’ve done better had he been born 70 years later.

For one thing, he might’ve noticed the fatal flaws embedded in socialism. It would be funny if, in time travel mode, he became some sort of Lyndon Larouche or Ron Paul-style zealot instead. On the other hand, he would probably just be publishing half-baked campfire tales about the Invincible Fed. When you think of it that way, maybe it’s a wash.

But the other reason I think he might have done better, and grown to become a true artist, is due to all the new market pressures and incentives he would face.

Evil Studio Head: Great work on that 1984 thing, Georgie. A critical darling, and the popcorn munchers loved it too! Now let’s talk sequel.

Orwell: Sequel?

ESH: Sure, sure. There’s gotta be a sequel, right? The bad guys got Smith right where they want him. Or so they think! We’ve got so many hooks to work with, too. What’s going on with the Brotherhood, for instance? And that Goldstein guy… what’s his deal?

O: He doesn’t exist!

ESH: Or that’s what O’Brien wants us to believe, eh? I’m thinking Jeff Goldblum for a nice, juicy cameo. Or is that too on-the-nose?

O: Okay, but my point was…

ESH: And then as a second act twist, maybe O’Brien shoots a blue laser into the sky, and turns Big Brother into one of those giant Japanese robot-things. Blam! Zap! Kapow!

O: Oh my…

ESH: And then this yuuuge CGI battle breaks out. Winston and Julia hijack a big spaceship. Zoom! Kerblammo! Rata-ta-ta-ta-tat! We’ll get those New Zealand guys on it. I hear they ain’t doing much business these days…

That’s the kind of divine punchline that lends itself to cosmic comedy: a depressive Brit’s pinko mindfuck, rescued from the abyss by Hollywood greed or Netflix serialization. 1985: The Brotherhood Rises could have been a smash hit! It also might have reminded audiences that “evil geniuses” like O’Brien and his gang are a dime a dozen, and aren’t nearly as invincible as they think.

Meanwhile, in contrast to the dystopians, we find popular authors who complete the hero’s journey unassisted. There are many who fit this bill, but perhaps none more so than J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. They tell whole stories, with whole endings, despite the threat of monsters and their masters.

That’s not to say they were either technically or morally superior to a great tragic artist like Dostoyevsky. I think the case can be made that Dostoyevsky produced the most morally significant artwork in living memory, but without resorting to preaching, or beating his readers over the head with “messages.” But the work of the Inklings is more accessible to the Western audiences they were written both about and for.

Tolkien and Lewis did not preach or program either. They instead told fairy tales, and in doing so gave birth to all modern conceptions of “fantasy” art. The monsters in their stories played their traditional role. They growled their warnings, scribbled their devious problems on the chalkboards. The heroes played their parts as well, enduring all tragedy, hardship and failure on the road to final victory.

In the telling, their artistic powers of prophesy not only remain intact, but exceed those of the dystopic crowd in every department. They can even see the monsters with greater clarity, owing to their desire to defeat them. Instead of agonizing over their awesome powers and bizarre anatomies, they point out all the weak hinges and Gordian knots, and demonstrate the best cutting techniques. That’s why I’ve sometimes taken to calling The Lord of the Rings a work of science fiction.

You could also call it a work of prophecy. Not quite the sort of prophecy one might find in Revelation, where narrative beats and poetic metaphor often blur into amorphous cloud-blobs, to be interpreted by Maji. The artistic prophesy of Tolkien and Lewis bends spacetime into a Möbius strip, while still remaining identifiably a story. It shows how all human stories spiral out of the same fractal, so that the present tense becomes just another iteration, with much the same choices and forked roads as any other. Middle Earth is our Earth, eternally cast. Narnia is the nexus of our pasts and futures. Lewis even experiments with the more “traditional” (but really novel) sci-fi form in his Space Trilogy.

In all of these artworks, we are shown monsters and heroes, problems and solutions. The science part of the sci-fi is present throughout, in the form of procedural exploration. It is not a question of Why, which is deeply known, but of How, which is often barely visible. You need to wade into the shadows, and squint hard.

You also need a ragtag band or motley crew. You’ve got a Saruman problem, you say? A Big Brother problem? A N.I.C.E. problem? That doesn’t sound so nice. Let’s team up and figure out how to solve it, shall we?

We should start by finding ourselves a really good teacher.

(excerpt from

’ “A Prophecy of Evil: Tolkien, Lewis, and Technocratic Nihilism”)But, crucially, Lewis argues the chest must be trained, exercised through by right guidance and repeated experience to grow and strengthen in its capacity. Mark, in his near total inexperience, got lucky in recognizing the Normal only through its absence. At its default the chest’s powers of discernment and judgement are typically weak. It must be trained to recognize and practice what “St Augustine defines virtue as ordo amoris [ordered love], the ordinate condition of the affections in which every object is accorded that kind of degree of love which is appropriate to it.”

For Lewis, this, more than training the mind’s ability to weigh material facts and calculate data, is the true purpose of education – or as “Aristotle says… the aim of education is to make the pupil like and dislike what he ought.”

And in this old way of education the virtues that teachers sought to inculcate in their pupils were derived from the hard won experience of wisdom accumulated by their tradition. They were “prescribed by the Tao” – a “norm to which the teachers themselves were subject and from which they claimed no liberty to depart.” They did not try to “cut men to some pattern they had chosen.” Instead they “handed on what they had received: they initiated the young neophyte into the mystery of humanity which overarched him and them alike.

In reading these sci-fi fairy tales, we’re also, in some sense, writing them. We are building our half of the bridge. We sketch the characters’ failures and fears, their courage and triumphs, across the pages of our imaginations. And while the end is “triumph over evil,” it is not “Happily ever after” as that’s commonly understood. It isn’t “All’s well that ends well,” either, in the mode of Shakespeare’s comedies. There is more than a quantum of mystery in their endings, just as there is mystery in the endings of our own lives.

Boats sail off to misted islands, leaving behind dear friends and homelands. Mythic beasts enter magic barns for judgment; some emerging as incoherent shadows of their former selves, and others moving on to undiscovered countries. Floodwaters drown all youthful illusions and simulacra. Beloved characters die in twisted wreckage, only to encounter the ultimate truth of existence.

And even after these so-called final revelations, mystery and possibility remain. Like the last frame of a horror movie, it’s not so much “The End” as “The End???” Whole human stories, but not The Whole Story. For who could tell that one but God Himself.

Our human versions have the heroes plunging into the darkness, to do battle with man-eating spiders and twisted ex-men and psychotic bureaucrats and more. They also battle themselves there, cross swords with their inner demons as much as they do the meat-and-bone variety. They sometimes fail and falter, as Boromir did at Parth Galen before his redemption, and as Frodo himself would fail standing before the fires of Mount Doom. They are heroes, but not perfect paragons or archetypes. We don’t need to squint hard to see ourselves in them.

But to descend into the pit is only half the trip, and half the lesson. Like a sip from the Pirian Spring, an aborted mission is worse than no mission at all. So, while 1984 is in some sense a “good” book, it sits more comfortably on that airport bookshop shelf, right next to the latest Stephen King (and even King will occasionally tell a whole story, and get the ending right).

The same goes for Lem, and Return From the Stars. It’s a good start, maybe. We are given much intrigue to work with, and some interesting characters to explore. On the other hand, you could say the same thing about that dumb TV show Lost.

Like Orwell, Lem has since passed beyond the Veil, so there’s not much hope for a sequel to set things right. But let’s play Evil Hollywood Executive, and give it a go.

Return from Hell

When last we saw Hal Breggs he was contemplating his old space adventures, and then closing the book on them forever. The story picks up with Hal sitting in a doctor’s waiting room. He has decided to submit himself to psychic castration after all, so that he might be closer to his beloved Eri.

While he awaits the procedure, and ponders all the feelings he’ll never experience again, a man walks in to meet him. It wasn’t Olaf, wasn’t Thurber with an armload of new plans for the Sagittarius mission. It was his old shipmate Tom Arder, the man they lost forever in the milky black chasm of an asteroid.

Or not quite forever, as it seemed.

He’s as big as ever, still looks like he could walk through a wall without noticing. And maybe now he could, Hal thinks, since he can’t possibly be anything but a ghost.

When Tom speaks, it’s with that same level tone, the telephone voice in the hotel room.

“Come with me. I need to tell you something.”

After they exit the hospital and climb into Tom’s gleeder, he begins to tell Hal about the true fate of the world, the hidden structure. He explains there is no such thing as betrization. The actual procedure will not just remove his emotions. It will remove Hal Breggs entirely, and install something else in his place. It turns out most of the people Hal has met since his return aren’t human beings at all. They did not “kill the man in man” as he surmised, but were never men to begin with. There had been an invasion of sorts, while he and Tom were away on their long mission.

When Hal demands an explanation for his own return, Tom takes a deep breath. He breezes through various procedural theories of time dysplasia and parallel dimensions, calmly dismissing each one as he goes. At the end, he looks at Hal with tears in his eyes. It’s the same look he gave him on the painted moonscape of Kereania, overcome with beauty as they tried to outwit Death.

“I think an angel saved me, Hal.”

The gleeder speeds off towards the horizon. They are set upon a new mission now. Not to the stars, but into the alien darkness that haunts their captured homeworld.

There will be more of them soon, a fellowship of sorts. More astronauts and other unfrozen savages will join their ranks, just itching for the chance to set things right. There’s also a fireman, a news editor, and a talking white pig with a porcine score to settle.

They keep coming and coming, rising wraithlike from the musty pages of unfinished masterpieces and psychopathic training manuals. It’s like Avengers: Endgame on seven tabs of mescaline. They all seem wiser for their journeys to the center of the night, and desperate for a proper ending to their tales.

And, with the right teachers and textbooks, they shall have them.

Now there’s a story for you.

Call me, Hollywood. Let’s do lunch. I hear you’re not doing much business lately.

The Cat Was Never Found is a reader-supported blog. I don’t publish much paywalled content, so your patronage is very much appreciated.

P.S. If you found any of this valuable, but cannot commit to a subscription, consider dropping some change in the tip jar, instead. It will also grant you access to my“Posts” section on the site, which includes some special paywalled Substack content.

I’ve never heard anyone invoke 1984 without also despairing of the inevitable tyranny.

Works that induce despair are visions from the dark lord in the Palantir.

If copyrights were less strict, novels that capture people's imaginations could be played with before that generation ossified. Authors could write sequels, strive to improve the originals, and so forth. The closest thing we have is for authors to write counter stories that most people will not be aware are a rebuttal.